Graphene: The quest for supercarbon

Graphene is, basically, a single atomic layer of

graphite; an abundant mineral which is an allotrope of carbon that is made up

of very tightly bonded carbon atoms organised into a hexagonal lattice. What

makes graphene so special is its sp2 hybridisation and very thin atomic

thickness (of 0.345Nm). These properties are what enable graphene to break so

many records in terms of strength, electricity and heat conduction (as well as

many others). Now, let’s explore just what makes graphene so special, what

are its intrinsic properties that separate it from other forms of carbon, and

other 2D crystalline compounds?

Fundamental Characteristics

Before monolayer graphene was isolated in 2004,

it was theoretically believed that two dimensional compounds could not exist

due to thermal instability when separated. However, once graphene was isolated,

it was clear that it was actually possible, and it took scientists some time to

find out exactly how. After suspended graphene sheets were studied by

transmission electron microscopy, scientists believed that they found the

reason to be due to slight rippling in the graphene, modifying the structure of

the material. However, later research suggests that it is actually due to the

fact that the carbon to carbon bonds in graphene are so small and strong that

they prevent thermal fluctuations from destabilizing it.

Electronic Properties

One of the most useful properties of graphene is

that it is a zero-overlap semimetal (with both holes and electrons as charge

carriers) with very high electrical conductivity. Carbon atoms have a total of

6 electrons; 2 in the inner shell and 4 in the outer shell. The 4 outer shell

electrons in an individual carbon atom are available for chemical bonding, but

in graphene, each atom is connected to 3 other carbon atoms on the two

dimensional plane, leaving 1 electron freely available in the third dimension

for electronic conduction. These highly-mobile electrons are called pi (π)

electrons and are located above and below the graphene sheet. These pi orbitals

overlap and help to enhance the carbon to carbon bonds in graphene. Fundamentally,

the electronic properties of graphene are dictated by the bonding and

anti-bonding (the valance and conduction bands) of these pi orbitals.

Combined research over the last 50 years has

proved that at the Dirac point in graphene, electrons and holes have zero

effective mass. This occurs because the energy – movement relation (the

spectrum for excitations) is linear for low energies near the 6 individual

corners of the Brillouin zone. These electrons and holes are known as

Dirac fermions, or Graphinos, and the 6 corners of the Brillouin zone are known

as the Dirac points. Due to the zero density of states at the Dirac

points, electronic conductivity is actually quite low. However, the Fermi level

can be changed by doping (with electrons or holes) to create a material that is

potentially better at conducting electricity than, for example, copper at room

temperature.

Tests have shown that the electronic mobility of

graphene is very high, with previously reported results above 15,000

cm2·V−1·s−1 and theoretically potential limits of 200,000 cm2·V−1·s−1 (limited

by the scattering of graphene’s acoustic photons). It is said that graphene

electrons act very much like photons in their mobility due to their lack of

mass. These charge carriers are able to travel sub-micrometer distances without

scattering; a phenomenon known as ballistic transport. However, the

quality of the graphene and the substrate that is used will be the limiting

factors. With silicon dioxide as the substrate, for example, mobility is potentially

limited to 40,000 cm2·V−1·s−1.

Mechanical Strength

Another of graphene’s stand-out properties is its

inherent strength. Due to the strength of its 0.142 Nm-long carbon bonds,

graphene is the strongest material ever discovered, with an ultimate tensile strength

of 130,000,000,000 Pascals (or 130 gigapascals), compared to 400,000,000 for

A36 structural steel, or 375,700,000 for Aramid (Kevlar). Not only is

graphene extraordinarily strong, it is also very light at 0.77milligrams per

square metre (for comparison purposes, 1 square metre of paper is roughly 1000

times heavier). It is often said that a single sheet of graphene (being only 1

atom thick), sufficient in size enough to cover a whole football field, would

weigh under 1 single gram.

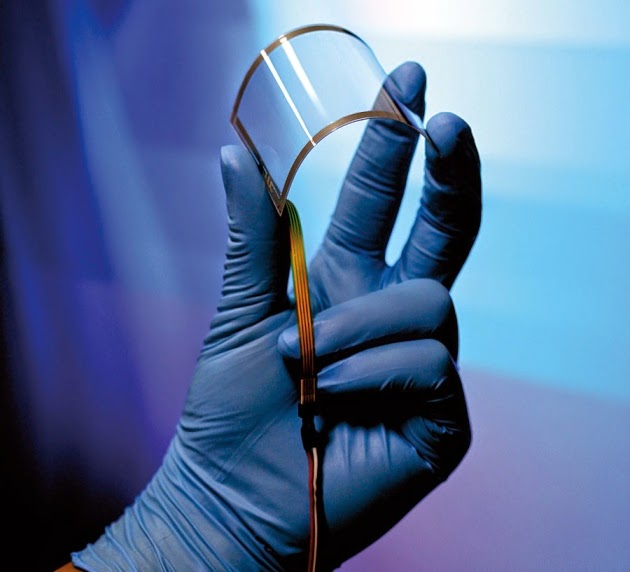

What makes this particularly special is that

graphene also contains elastic properties, being able to retain its initial

size after strain. In 2007, Atomic force microscopic (AFM) tests were carried

out on graphene sheets that were suspended over silicone dioxide cavities.

These tests showed that graphene sheets (with thicknesses of between 2 and 8

Nm) had spring constants in the region of 1-5 N/m and a Young’s modulus

(different to that of three-dimensional graphite) of 0.5 TPa. Again, these

superlative figures are based on theoretical prospects using graphene that is

unflawed containing no imperfections whatsoever and currently very expensive

and difficult to artificially reproduce, though production techniques are

steadily improving, ultimately reducing costs and complexity.

Optical Properties

Graphene’s ability to absorb a rather large 2.3%

of white light is also a unique and interesting property, especially

considering that it is only 1 atom thick. This is due to its aforementioned

electronic properties; the electrons acting like massless charge carriers with

very high mobility. A few years ago, it was proved that the amount of white

light absorbed is based on the Fine Structure Constant, rather than being

dictated by material specifics. Adding another layer of graphene increases the

amount of white light absorbed by approximately the same value (2.3%).

Graphene’s opacity of πα ≈ 2.3% equates to a universal dynamic conductivity

value

Due to these impressive characteristics, it has

been observed that once optical intensity reaches a certain threshold (known as

the saturation fluence) saturable absorption takes place (very high intensity

light causes a reduction in absorption). This is an important characteristic

with regards to the mode-locking of fibre lasers. Due to graphene’s properties

of wavelength-insensitive ultrafast saturable absorption, full-band mode

locking has been achieved using an erbium-doped dissipative soliton fibre laser

capable of obtaining wavelength tuning as large as 30 nm.

In terms of how far along we are to understanding

the true properties of graphene, this is just the tip of the iceberg. Before

graphene is heavily integrated into the areas in which we believe it will excel

at, we need to spend a lot more time understanding just what makes it such an

amazing material. Unfortunately, while we have a lot of imagination in coming

up with new ideas for potential applications and uses for graphene, it takes

time to fully appreciate how and what graphene really is in order to develop

these ideas into reality. This is not necessarily a bad thing, however, as it

gives us opportunities to stumble over other previously under-researched or

overlooked super-materials, such as the family of 2D crystalline structures

that graphene has born.

ReplyDelete3d printing materials

3d prototyping

3d printer filament

3d printer filammapmyindia gps trackerent